Now that we have a structure in place, lets see what other functions we can add.

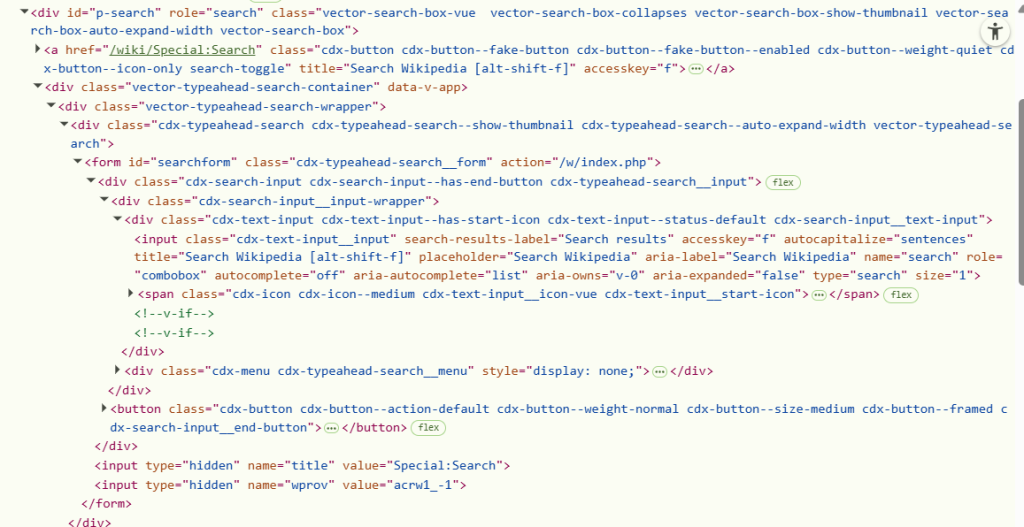

What is a website? What components make up a website? What do we do with websites? Take a moment to go back into that developer tools window in your web browser (Right click -> inspect, or F12). What type of elements do you see?

Apart from the nested elements like forms or divs, the page boils down to a few types:

div: A generic element, frequently containing classes and text.input: A form to input information, like or radio button or text.span: A generic element, frequently containing classes and text.a: A hyperlink… frequently containing classes and text.label: A generic element, frequently containing classes and text.button: A button (containing classes and text).

This isn’t an exhaustive list, but you’ll notice that the type and action don’t map directly onto each other. The point is that you’ll see things you don’t expect and to keep your solutions behavior-oriented. If I had a nickel for every time I saw a div that was masquerading as a button…

So then, thinking about it the other way, what behaviors happen on pages?

- Validate Text: Read the text on a page.

- Enter Text: Type keys into a form.

- Click: Click on a link, button, or other element. Could be a double click, right click, drag and drop, etc.

However, the actions can have overlap on an element. A button can be clicked and the text on it validated. A textbox can be typed into as well as clicked. Selenium gives us these methods for doing basic operations, but what do we do when we start to need complicated operations?

Functions for Complicated Web Elements

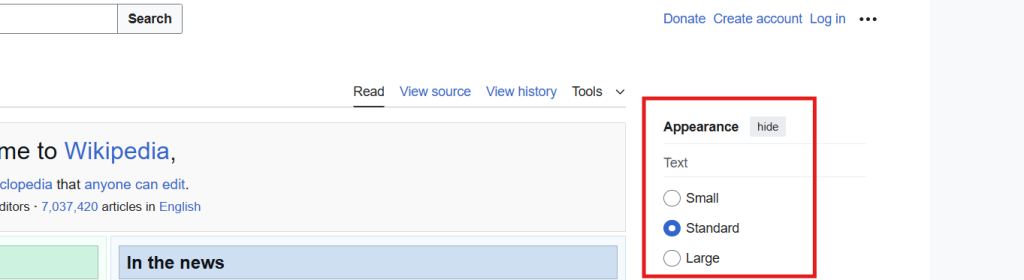

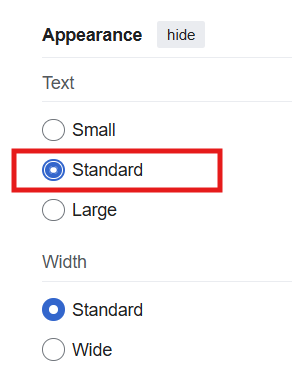

So far we’ve kept things simple. Enter text, click the button, check the URL. That covers most of what we need to do in a webpage. Lets take a look at something more complicated – look to the right of the page at the appearance settings section.

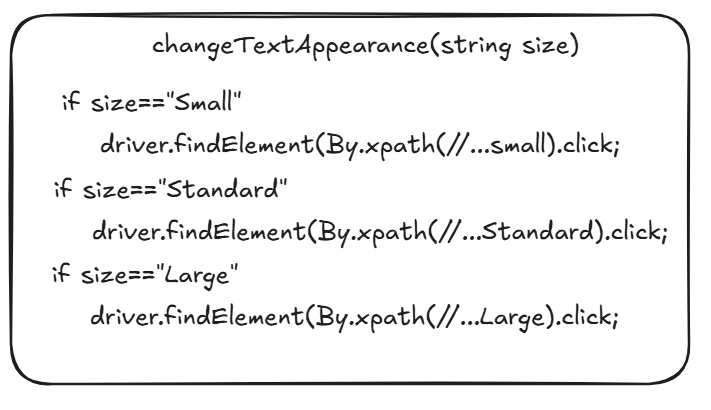

That radio button for text appearance alters the size of the font on the page. Pretty cool! Let’s say that we want to automate it as part of one of our tests. Conceptually, how would we do that? We could make a function to click each button there, makeTextSmall, makeTextStandard, makeTextLarge. But that feels bloated – like we could consolidate it. Instead, we could make a function called changeTextAppearance that takes in a string for small/standard/large and clicks the appropriate button. Okay, seems simple. Let’s pseudocode it it:

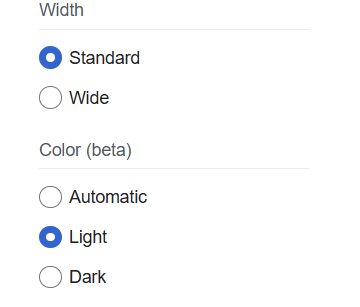

Something like this? Okay, let’s look a little further. What other appearance options are there?

Two more settings with 5 more options between them. That’s a lot to map out. It’s not difficult to automate, we’ll just need to code a handful of element calls. But what if there were 20 options? What if there were 50? Where do we draw the line on this tedium?

Where do we draw the line on this tedium?

Honestly, I draw it pretty early on. If we can setup a system that will work into the future, it’s usually worth implementing. I do recommend waiting for a few examples to emerge before looking for a solution, since you never know the full scope of the problem at the beginning. Over-engineering a solution when you aren’t fully confident of your needs can cause a lot of heartache and wasted time when you need to start over.

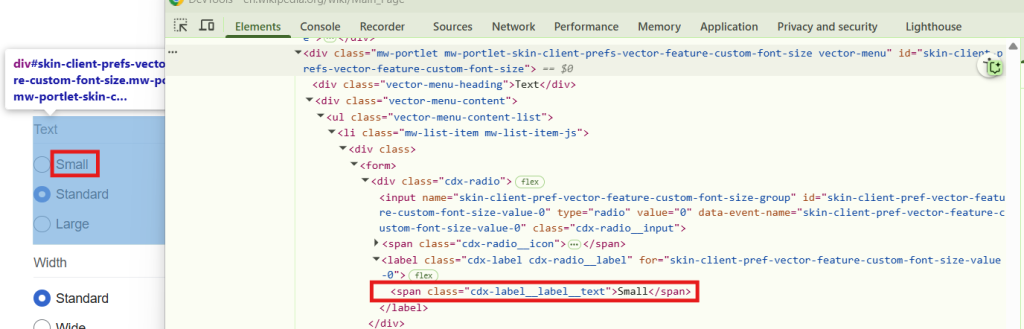

I’d say that three-ish examples is a good place to start. Our question can be: “how do we automate radio buttons?” Well, we know the heading of the menu (text), and the button names (small/standard/large). So really what we’re saying is: on this menu, click the button with this name. Can we find a logical way to deduce the button’s labels? Let’s check the back end.

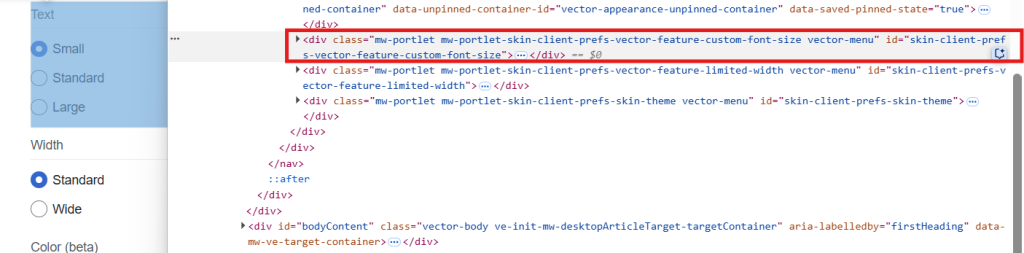

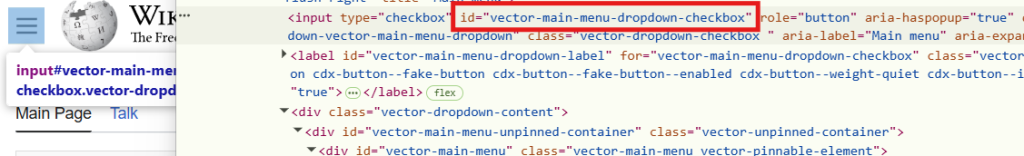

The blue highlight is the top element in the devtools.

If you poke around with the HTML and interact with the browser, you’ll notice that clicking on the text for small, standard, and large perform the resizing action. In other words, if the element text is “Small”, click on it. If we check back into the Seleinum Javadocs, we’ll see that there is a function for getText on an element, but we would need to have the element first before we checked the text. Here’s a useful trick for you – on the xpath cheatsheet that I shared in an earlier part, you’ll find an example of text matching. Instead of knowing the element that we want to interact with, we’re finding the element that meets our criteria.

//span[text()='Small']

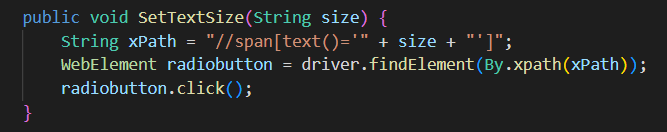

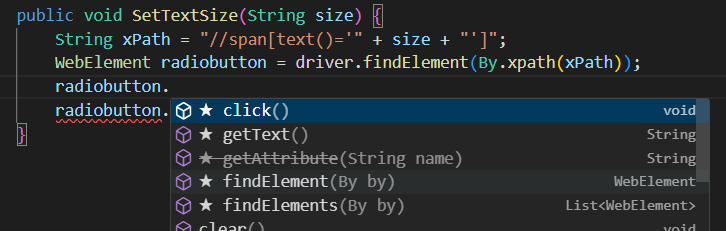

Let’s try putting this into a test and see if it works. Let’s make a new function for clicking the radio button that takes in the size as a String and uses that to form the xpath. There are a few different ways to do this, but I think the most straightforward way is by adding them together via concatenation. In Java this is done like an actual addition statement, where new string = string 1 + string 2.

Here’s what I get:

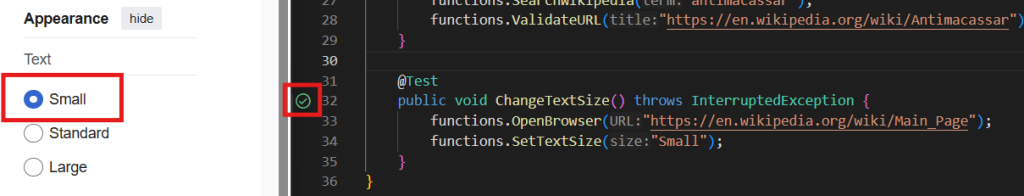

It works for me! And… probably for you? I suppose there is a small chance that there is a different element on the screen whose text is “Small” that could be getting clicked instead. Speaking of which, what if we wanted to click the Standard option?

Fortunately we’re clicking the first element we see that matches, but in this scenario there are two that match. Since our logic will be the same for interacting with the Width radio menu, we need to change it to accommodate this edge case. How can we prevent it from clicking the first button? Do we add an option that tells the function to click the second instance?

SetWidthSize(String width, int instance)

This way we can call SetWidthSize("Standard", 2) and It’ll know to find the second instance of “Standard” on the page… but that doesn’t solve our problem in a very elegant way. Lets put a pin in that idea for handling multiple elements at once. Adding these band-aids to edge cases means that our logic was wrong in the first place. What else can we do?

Scope and Sub-Elements

Our logic was good, but it’ll be hard to apply that anywhere on the webpage. You never know what might throw a wrench in it. Rather than try to contort our logic to work anywhere and everywhere, we can change our perspective of where it is applied. We need to narrow down the scope that we are searching for elements within.

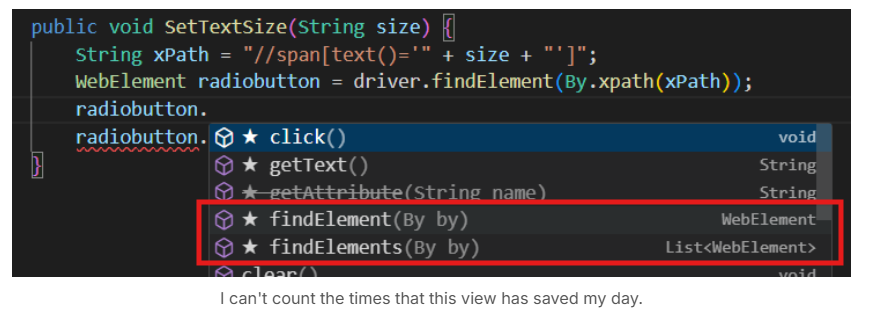

With Selenium it is possible to search for an element from an element. Grab an element object and check out what’s available from intellisense:

If we find an element that encapsulates all of the radio button options for the menu and then search from that, we should find the correct element. Lets go back to the devtools:

The three div elements here seem to fully wrap around the radio buttons that we need. If we can find selectors for these elements instead, we can apply our existing logic to that element for a consistent result. Between these three divs, what differentiators jump out to you?

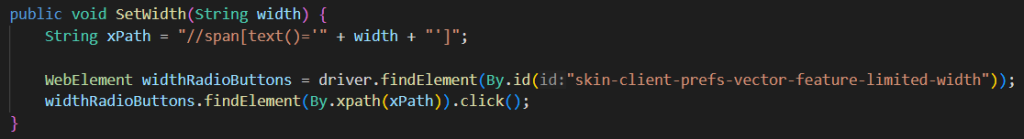

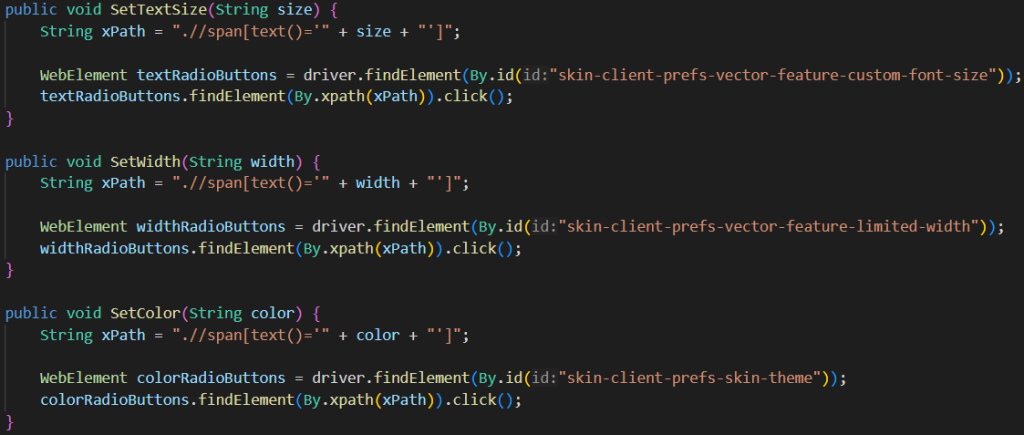

This is another situation where there are a lot of correct answers. I’d recommend browsing the options found in the intellisense for the By class to see what’s possible. To me, the IDs stand out. Here’s what my function ends up looking like:

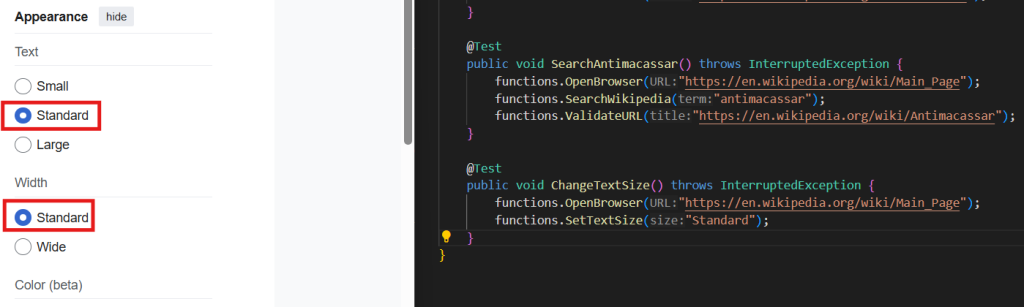

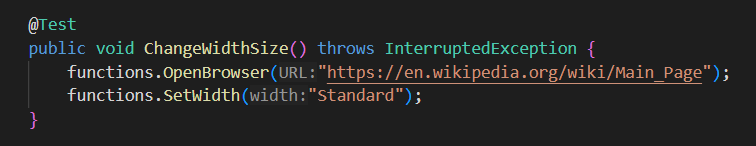

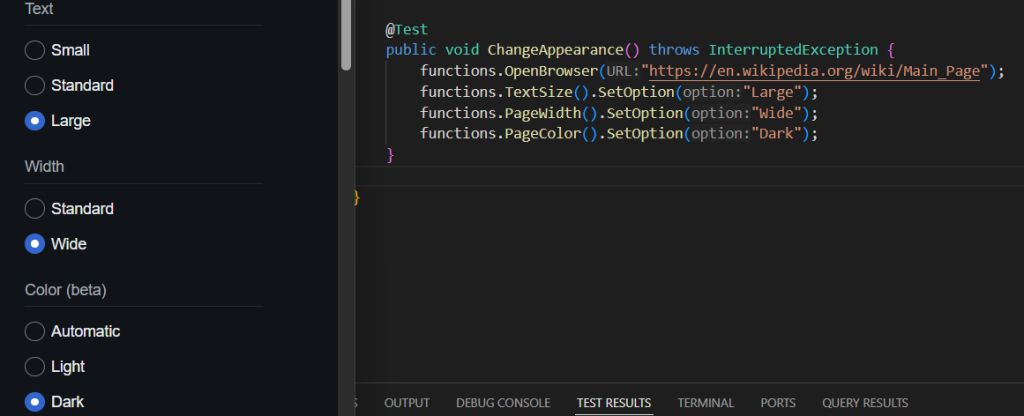

My test for the code looks like this:

It might be hard to tell, but after running it I have an issue. I can see from the UI that it still clicked the first instance of “Standard”! What gives?

On the xpath cheatsheet we learned that the prefix // means “anywhere on the page.” In this case, that overwrites our goal to limit the scope. When doing any kind of relative xpathing, you can use a . to denote that this should be a relative xpath. We can use .// to indicate “anywhere from the current node.” keep in mind that xpaths are powerful and leave you a lot of room to make mistakes.

After adding a function for the Color and updating the Text Size radio buttons, my code looks like this:

The sleuths among us might notice that there is a repeated logic pattern here. We start from an element and identify a button to click with it’s text. This is behavior that unique to radio buttons, and we will want to duplicate for all future radio buttons. What is the best way to organize this?

Creating a Radio Button Class

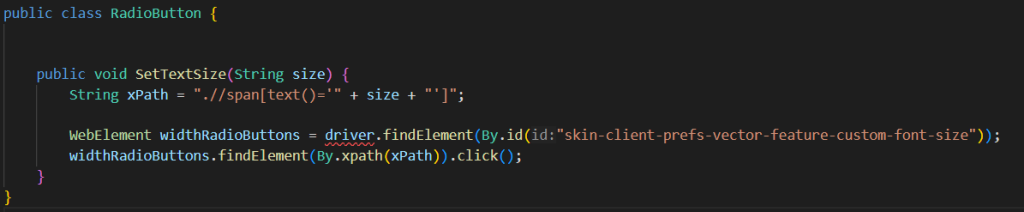

Let’s make a class for it! Just like how we moved our Selenium functions into their own class in the last article, we can move all of these into a new RadioButton class. Start by making a new java file in the example folder for it, called RadioButton.java. We already know we want to use this setOption logic to select any radio button by name, so lets copy and paste right over that whole SetTextSize function to help us visualize what we’ll need.

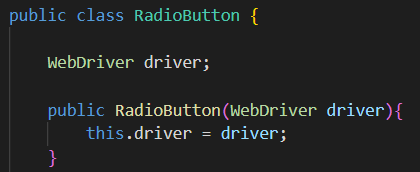

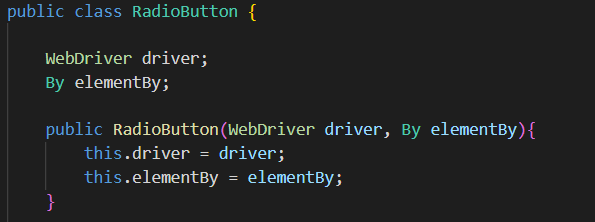

The red squiggle reminds us that we need to have a driver in context to do this. Therefore, we’ll need to have some way of passing it in and storing it. Like in SeleniumFunctions, I added the WebDriver as a member variable of the class. But how can we pass it in? Classes have a concept of their first time setup, called a constructor. Just like how we send values into functions, this lets us send values into classes. The syntax for these is a little unusual: it is a public function with no return type whose name is the exact same as the class. In our situation we need to accept a WebDriver, so in this case it’s: public RadioButton(WebDriver driver). Inside the function we can set our class’s driver to the one that was passed in:

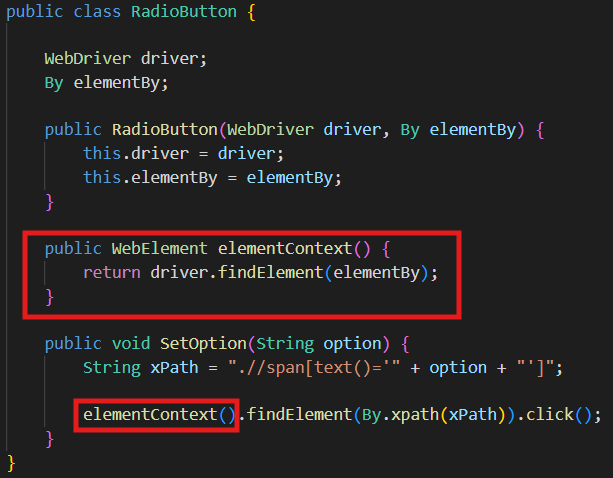

Next, let’s look at the function again. We can change the title from SetTextSize -> SetOption and the size variable into option to make it more generic. After that, our code finds the context element to search from. How can we make this more generic?

One solution is to pass that selector into the function call, so that SetOption is accepting both the context and the button name. How does this scale? Consider a function that validates the radio button that is currently selected. Our ValidateOption function would also need to accept the selector to determine that. Any function that has to do with these radio buttons will need to know the context, so we might as well make it a class variable too.

This too has a few different and valid ways of implementation. You could find the WebElement object and pass it directly into the class. You could just pass in the id that we found as a string. My recommendation is to pass in the By object entirely, so that the object knows enough information to find itself if it needs to.

Finally, we need to connect the dots on the elementBy and the context element that we create inside the function. We need some way to generate that context within our class – a simple method that returns the element found by the locator. Add a function that returns the WebElement using the driver and elementBy that we already have, and substitute that into the SetOption function:

Now that the class is finished, we need to implement it. Where? Excellent question. Although it’d be nice to create it inside the test library directly, it needs to know what the WebDriver is, so it needs to go inside the SeleniumFunctions class. That’s an interesting thought though – lets put a pin in that for later.

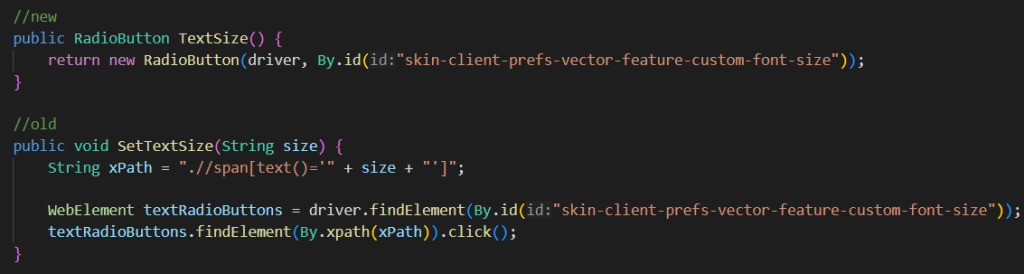

To create this object, we need to setup a public function called TextSize() (or, you know, whatever you want to call it) that returns a new instance of a RadioButton using the constructor we setup, which needs the WebDriver and By. Here is a comparison of the implementations:

Then, instead of calling that SetTextSize() function in the test we can access the TextSize() function from the SeleniumFunctions object, then call the setOption function after TextSize:

functions.TextSize().SetOption("Standard");

Why is TextSize a function instead of a class variable?

Excellent question! It makes more sense to just make a variable instead of a function, right? The problem comes in with the timing of the creation of the WebDriver instance. You can try it out yourself – it’s good practice. If TextSize is a RadioButton variable that belongs to the SeleniumFunctions class, it’ll get created at the same time that SeleniumFunctions does. In that case, the OpenBrowser function has not been called yet and so the driver variable that we pass into TextSize has not been instantiated yet, and since it has no value, the driver doesn’t work. Bummer. Another interesting idea though, put a pin in that too.

Once you replicate this pattern for each of the radio button groups and update the By selector for each, you have a mechanism for changing all of the appearance settings without needing to map out each of the buttons.

Solving problems programmatically with logic instead of “hard-coding” every possible option creates solutions that you can mentally and emotionally put down once you’re finished with them. Now, the next time you see a radio button on Wikipedia, you can have some confidence that you’ll be able to automate it using this logic.

We did a lot of designing during this article, and we put some pins in a few interesting ideas. Let’s revisit those.

Pins: Element Lists

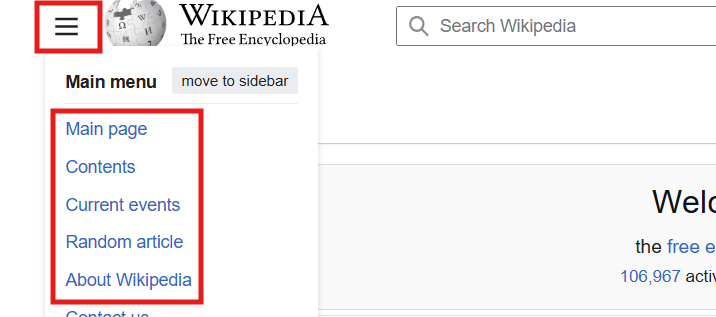

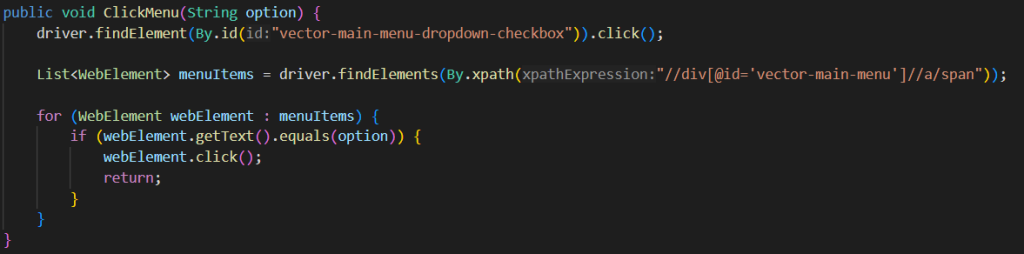

Remember when we were finding two matching elements that had the text “Standard” in them? There may be some cases that we want to get all the elements that meet a criteria and then check a property on them to find the element that we were looking for. Lets take the Wikpedia main menu as an example. Click the three bars (called a hamburger menu) to the left of the Wikipedia icon and observe the main menu:

If we wanted to automate selecting something from this main menu, one solution would be to click the button, find the text we want, and click on it. If we wanted to model that as an object, we would need a selector for that button and one for all of the menu items. We could use the same logic as before where we use the text inside the xpath. Totally valid!

Let’s make things a bit more interesting. Let’s say we want to verify the text on the element before we click on it. Suddenly, we need to keep some context of all of the elements inside of the menu and have a way to traverse through them. Hang on, I’m having a flashback to the start of the article:

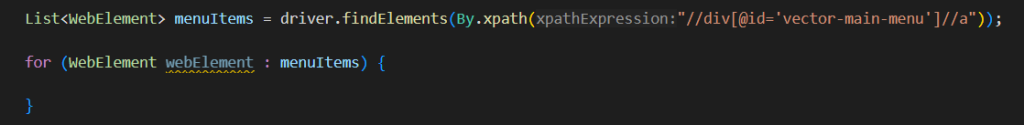

In addition to the findElement() function that we used to get a WebElement, there is a findElements() function that returns a List of WebElements! A Java List is a way to organize a group of the same type of object (in this case, WebElements) with ways to search and move through them. If we had used this function earlier when we had two matching objects, it would have returned them both for us.

Lets try creating this menu function. We’ll start by sending a click to the hamburger menu to open up the options:

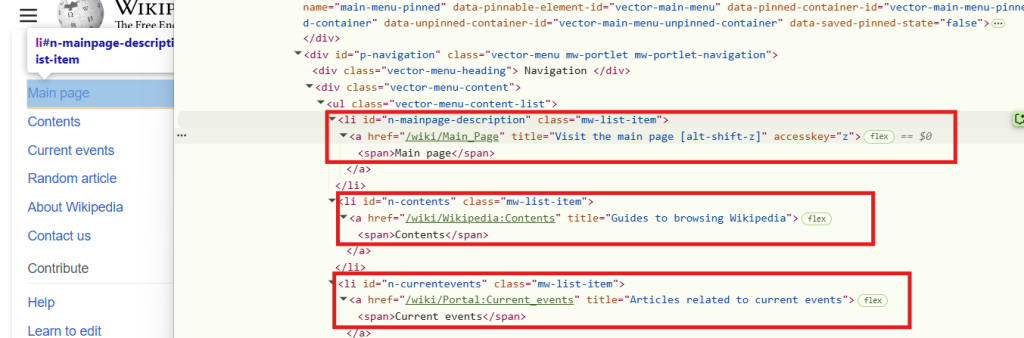

Then, we can start to investigate a pattern that will work for each of the menu elements. It’ll take some time to work something out, so enjoy the exploration.

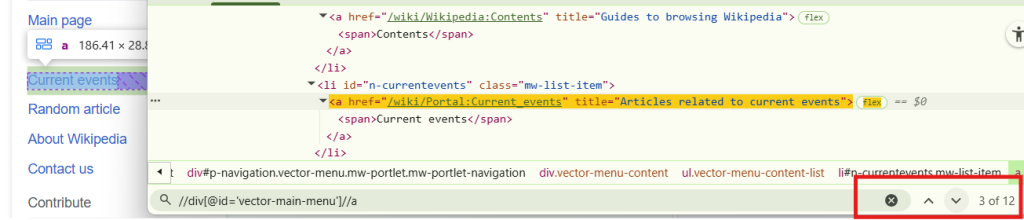

Once you see a repeated pattern like this, you can start to craft an xpath that’ll work by pressing ctrl+f in the devtools to bring up a searchbar. When doing this kind of search, I recommend anchoring the xpath onto an element that encapsulates what we’re looking for. I started with an xpath like this:

//div[@id='vector-main-menu']//a

From the view, it looks like we found the correct amount of elements. Flipping through them seems to highlight the right elements. Let’s roll with this for now. We need to create a new List<WebElement> variable and set it to what we get from our selector. Then we’ll need to search through each of the elements to find which one has the first text value. We can do this with a for-each loop, a variation of the for loop that you might be familiar with. It looks like this:

Then, to check the text on each of the elements, you can use the getText() function. If the text on the element is equal to the value that we were looking for, we can click it. Once we find it, we can stop searching and exit the loop by calling return.

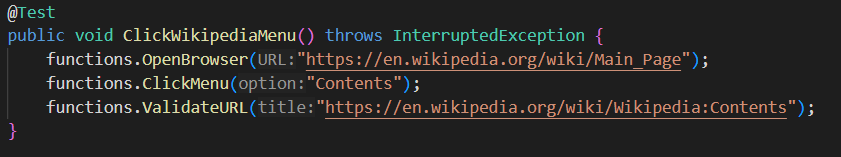

Here’s another test to use this function:

You might notice that the speed of developing new tests is starting to ramp up. We’re identifying new functional pieces, adding logic, and incorporating them to our framework. When taken in small bites of work, code is much easier to manage.

Pins: Where does the Driver go?

There were two instances in our code where we wished that the driver was created somewhere else; we wanted to create the RadioButton class inside the test and then we wanted to turn the RadioButton element into a class variable instead of a function.

The reason that we couldn’t do this is because the driver is tightly coupled to the SeleniumFunctions class. The OpenBrowser function has to happen at the start of every test anyway, and we want to be able to use the driver elsewhere. What’s happening is that SeleniumFunctions is carrying too much weight and is responsible for more than it should be. If we had a new class that started the webdriver and then passed it into the other classes that needed it, we would be able to reorganize the functions and scale things out differently.

This is going to get complicated, so take some time to feel comfortable with what you’ve learned so far. Try putting the driver somewhere else and see what patterns start to emerge.

Leave a Reply